IN PRIMA LINEA

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

Within the boundaries of the history of photography it is easy to trace the steps of a predominantly male and western practice that shaped this medium into a dialectic discourse between the subject that holds a voyeuristic power over the portrayed object.

In India the initial period of presence of photography is mainly devoted to the prosecution of the activity of mapping the South Asian region in its different aspects, operated both by western people in India and quickly after by Indian photographers themselves. Maharajah Ram Singh II extensively portrayed courtesans and people around him as well as concentrating on his own self-portraits in different guises and dresses. His photographic research is very much devoted to the restitution of images that depict the wealth and refinement of people attending his court as well as investigating his multifaceted identity, composing accurately the scene for the best aesthetic outcome. The portraits of Ram Singh II stand out for their psychological depth as well as for their rarity, documenting something usually not allowed or encouraged.

It is possible to come across a staged photograph in the photographic studio in Bombay of Shapoor Bhedwar, a prolific professional that concentrated his activity in depicting portraits of wealthy families as well as staging original and fictitious scenes with a language that appears closer to a pictorial rather than photographic production. In this latter case the subjects are stripped of their identity and serve in the portraits as bearers of meaning, as subject of a built narrative or a staged performance for the camera with the same theatricality of gestures that one would expect to see either during a theater play or in a historical painting.

On the basis of these initial steps in the history of photography in India by Indians should be understood the production of the contemporary photographer Gauri Gill and in particular her series Acts of Appearance, realized in the villages of Maharashtra, ongoing since 2015.

In this series Gill dialogues with the recent tradition of papier maché mask production that is common to different tribal villages in Maharashtra, after having investigated in other previous series and researches local tribal traditions and their photographic counterpart. Gill’s interest in this craft had its origin in her participation in the Bohada festival, a recurring event for Warli and Kokna tribes in which deities are celebrated through a joyful and animated procession in which village people impersonate them by wearing masks of their stylized representation. The idea of focusing on this craft most probably stems from her permanence in the village when she was hosted by the artist Rajesh Vangad, an occasion to learn more about Warli culture and their artistic tradition, ultimately developing her own mature style and her research interests on this dialogue. In collaboration with Bhagvan Dharma Kadu and Subhas Dharma Kadu (two brothers that inherited the procedures and skills from their father Dharma Rama Kadu, the best known mask maker in the region) her idea for this series was not to replicate a traditional craft for the camera but rather a creation of new products that would create a dialogue with Gill’s photography and coexist autonomously as independent works of art within each other. The Dharma Kadu brothers invented new characters – not usual avatars of Hinduism but avatars of human emotions, animals, and everyday objects. Gauri Gill’s idea was to create a new narrative where the agents were not referring to a mythological past but set in the present. Masks represent human characters that express singled out emotions, conspicuously showing facial features that allow an easy recognition. As she discussed in an interview, her intent was to represent the nine Rasas, the emotional states of mind from classical Indian aesthetic theory but also other non-human subjects. In these photos, one recognizes immediately a certain degree of artificiality, something strange with the features of documentary or ethnographic photographs but an estrangement is aroused by the masks that do not match the bodies wearing them.

To be worn comfortably, the masks are necessarily larger than the actual size of a human head, the degree of detail is not sufficient to induce the illusion of reality and ultimately they arouse alertness in the viewer. In this sense we understand the practice of Gill in building a narrative and a composition in each image, using the visual lexicon of anthropological photography applied to expertly organized images, creating a mismatch between the expectation in the viewer and what actually appears in the shot. Through the presence of these masks, building a new individual and recognizable style, shere-appropriates anthropological photography, claiming an untold, fictional narrative that finds in the realm of contemporary art absolute freedom and possibilities of expression. This parallel mythology to the traditional Bohada counterpart is not limited to human emotions and animals but entails to a smaller degree also objects of domestic and everyday consumption. For example, in Untitled we can see how the mask worn by the man depicted is a television showing a car that is moving in front of skyscrapers while the subject depicted appears in front of the original model of television.

This duplicate, unlike any other image in the series, is a tangible witness of the innovation brought by this project. The realization of a television that supposedly is present in the homes of the Jahwar community represents the will to update the symbols of the Bohada procession to a secular reflection on what are the new idols, and what should be the contemporary version of this tradition. Gill makes the mismatch between traditional crafts and so-called metropolitan art evident. The mask appears detailed, yet not to a degree to be taken as the original. This contrast is made clearer with the television behind, showing how the notion of Adivasi and tribal life does not necessarily mean avoidance of the use of types of media that would not normally be associated with the Warlis or the Kokna. In this regard modernity wears the form of traditional crafts. This successful tension denotes a real sense of contemporariness of the people represented. They understand their position in the world, are aware of their identity and decide to not comply entirely to the urgencies or the changing nature of the globalized world. As philosopher Giorgio Agamben says:

“Those who are truly contemporary, who truly belong to their time, are those who neither perfectly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands. […] Naturally, this non coincidence, this “dys-chrony”, does not mean that the contemporary is a person who lives in another time. […] An intelligent man can despise his time, while knowing that he nevertheless irrevocably belongs to it, that he cannot escape his own time.”

Analyzing Gill’s series, we perceive the degree of contemporaneity based on this definition. The aesthetic quality appears to be referring to precedent works in the history of photography when compared to productions that feature the depiction of masks.

An immediate comparison could be made with the photos by Erich Consemüller titled Woman wearing a theatrical mask by Oskar Schlemmer and seated on Marcel Breuer’s B3 chair from 1926, that depicts a masked woman that appears to be looking at the camera, enjoying the comfort of the iconic piece of furniture by Breuer. Schlemmer, famous for his Triadisches Ballett, a work of performance inspired both by echoes of Surrealism and the aesthetic of the Bauhaus, investigates the role of masks in performance but also their capacity to make people anonymous to serve the purpose of the creation of a prototype, in this case a modern woman using state of the art furniture while wearing contemporary clothes. By losing her identity she can enter an ethereal dimension that allows an identification in the viewer. This operation of partial occultation of identity is operated by Gill, obscuring all the faces of the people depicted, achieving a universal language of emotions as well as including animals interacting with anthropomorphic figures. The improvised actors are conveyors of a message that oversteps them but at the same time involves their identity in this depiction, involving every member of the tribe into this secular mythology but also suggesting their silencing, being under these masks that do not allow any sensorial activity. The element of the mask can be traced back to the origin of performative arts in the West within the context of Greek theater, where masks were fundamental to suggest the emotions felt by the characters of the plays. With the use of the mask Gauri Gill seems to join and keep together different performative traditions, not only the one linked to the Bohada festival but also all the theatrical heritage of the ancient Greeks, introducing in some way an element that sees her art as catalyst of cultures that appear very different but can be reconciled when looking back into the history of India.

The performative nature of Gill’s photos can be seen in the examples that feature people carrying out activities rather than those who have a frontal take on a person posing for the camera instead of acting. The work Untitled (98) appears to be particularly interesting as it quotes openly the most traditional mask production. It represents a traditional trope of the Bohada festival that is the fight between Good and Evil, featuring a woman impersonating a female deity that is defeating a demon, lying on the ground. The context shows the rural appearance of the village and the bright colors of the figure on the left contrast with the brownish colors of the huts and the soil in the background. The realization of the masks does follow the bright colors usually employed by the Kokna and Warli, employing also a standard disposition and shape of the facial elements and accessories. The face of the deity is smooth and simple, her eyes are oval and long with white sclera contrasting with the tonality of the skin. She wears a golden headgear while being contoured by a decorative element. Gill is going back to the original mythology and captures a scene that in some way does not fit into the larger series of her, but at the same time excludes any desire of documentation of the original procession, following the same degree of orchestration and composition. The scene’s outcome, like any other in Acts of Appearance, is artificial and decontextualized from the event that comes originally from, showing nonetheless the importance of craftsmanship and ritual within the village context even in contemporary times. This particular photo, although appears as separated, is continuing to deal with a contemporary mythology for the Adivasi tribes of Jahwar but confronts the relevance that still persists of this art production, appearing as contemporary as a television or another electronic apparatus.

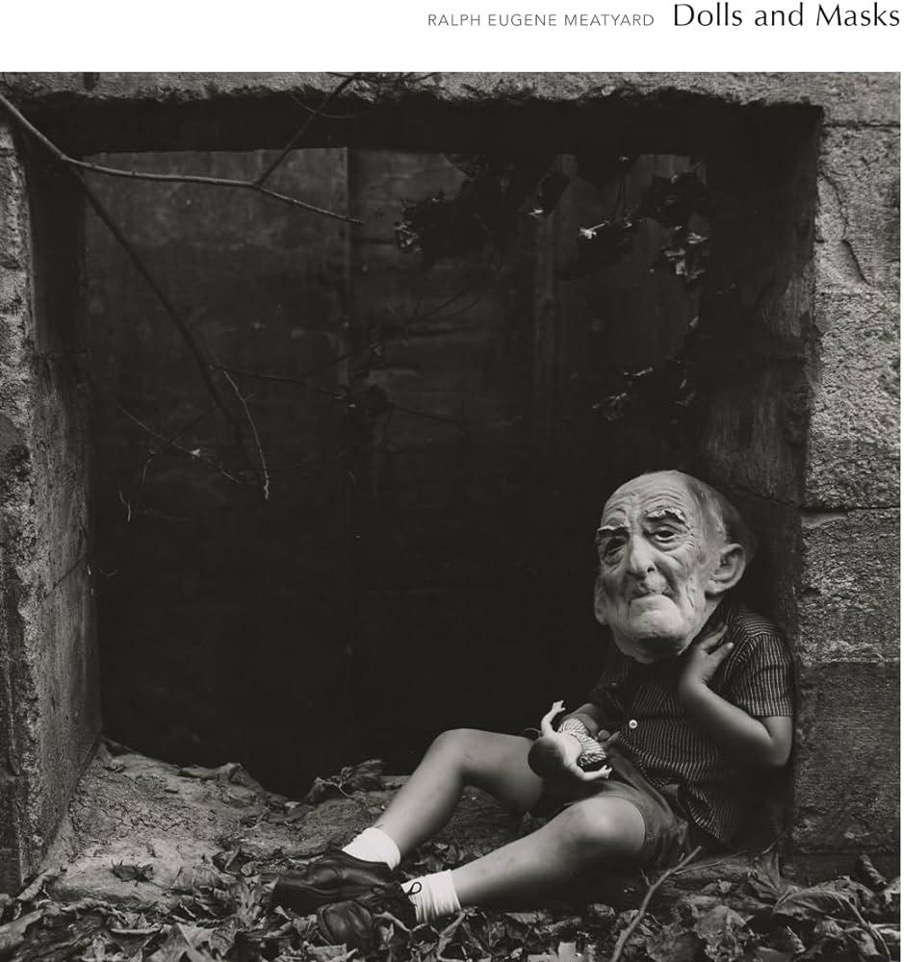

The mismatch between the body and a mask in Indian performative tradition doesn’t coincide with the duality of body-mind as it is in the western tradition and can be found conspicuously in other pages of art history such as the American photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard. In some of his series, he created uncanny staged images with silicone faces worn by characters. There is a certain degree of resemblance between Meatyard and Gill’s photos: when capturing normal actions with the disturbing defacing element of the mask a level of familiarity is combined to one of disorientation. When in Meatyard the tone appears to be at one time humorous and at another frightening thanks mostly to the black and white and the slightly underexposed outcome, as it happens in the series The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, Gill’s Acts of Appearance series inspires an atmosphere of joy and playfulness that is closer to a carnivalesque farce rather than a sinister vision. This is principally done by the easily understandable facial expressions of the masks, a clear composition, the presence of animals executing human activities as well as the presence of color – important to set the emotional climate of the image. In this series Gill cedes to the temptation to avoid color photography in order to imprint a positive message and consequently affect the Adivasi artistic and artisanal production that would not otherwise be understood.

Gauri Gill is able to reunite in her series apparently distant cultures, inserting herself into the global history of art, aware of the Indian and non-Indian development of photography that allows her to layer with multiple meanings her artworks both on the level of the subjects portrayed and the technicalities of the medium itself. She interacts with traditions and Adivasi contexts employing the device of the series – the photographic equivalent of the repetition often associated with tribal and folk art, developed through centuries. By the reiteration of similar photos, she creates homogeneous, yet diverse, bodies of work that find their unity into the dialogue between a metropolitan individualistic art and a collective identity found in the Warli culture. Gill is able to keep together also the environmental issues affecting the village that she visited and the modernity that is either imposed or necessary to the life of the Jawhar tribal people. She joins the mechanical outcome of photography to the physically produced and anthropologically cultural art of the Warli and Kokna and thrives in renovating the visual language of this region of Maharashtra, opening it up to the rest of the world. By taking up the pressing matters of identity representation, progress, tradition and cultural conflict or reconciliation, Gill succeeded in the hard operation of being truly contemporary.